Are All Activist Swarms Good?

How the 'multitudes' of Hardt and Negri have become the left's internecine zealots

While working in a bar in Berlin some radical feminists described to me in detail the scripted harassments of a feminist network there. The victims were always British, and they were often forced out of Berlin after relentless abuse, sometimes lasting years. They claimed in the bar that it was because the men hated German women, but I had already heard the rumours of British men being targeted for cheating as well. All the victims are either picked up in bars or on Tinder while they are single. In which case they might be filmed during sex, drugged, robbed, or sexually assaulted. The victims could also be entrapped into a relationship of scripted abuses, or in a flat share where the live-in landlady is part of the harassment, but also by a colleague planted in the workplace.

All of this is coordinated by one group who can use these women to nudge the Brit to apply for social housing. When he miraculously skips the que of people waiting for years for a flat, and is offered a flat on his first viewing, this is because he is being housed in a flat set up to drug him. He will also be harassed by neighbours. For the whole story, you really need to subscribe. What I am getting at in this post, is that when the victims flee back to the UK they are confronted with a scripted scene of harassment that will have been foretold them in Berlin. I was foretold the script verbatim, before experiencing the performance in Glasgow years later:

I was working on a book shop in the West End, having not long returned from Berlin, when the manager made a tenuous link to the topic of the killer Japanese wasp that was killing bees in America. My ears pricked up in anticipation. He explained, ‘because it is not native there the bees have no defence mechanism, but in its homeland, they knew how to deal with ‘him'’. All of a sudden two of my colleagues came from the other side of the shop to stand either side of him. All three stared straight at me, from 2 meters in directly front, “what they do is they gather round him and don’t allow him to breathe and they suffocate him, and the heat he feels is to much, and eventually he is cooked and dies.”. The three of them held their stare, grinned, quite pleased with themselves, and separated without another word.

This performance was as promised me in Berlin and it is what you call a swarm. Taking itself very literally- announcing itself as a swarm while performing a swarm. This is what modern activism is all about, the myth of leaderless, violent action for social justice.

The concept of ‘swarm’

In a previous post I argued for the importance of Joreen Freeman’s, The Tyranny of Structurelessness and it’s prophetic warnings over the myth structureless activism. This is a myth that social media has long heralded, and one that is now long incorporated into the myth of many activists. Freeman argued that “structurelessness” has the same destructive effects on feminism that are now being amplified by social media ‘networks’, or ‘swarms’. The Catalan sociologist coined the term ‘networks’ at the beginning of the century to mark the shift from pyramidal structures of bureaucratic organisations, such as the state, the party, the company, to horizontal organisations. The term network was chosen because it emphasizes the decentralization of the social, since ‘by definition a network has not center’ (Castels 2000:15). However, the theory was criticized for being a static model, a model of simultaneity. What was needed was a theory of flows and movements, and it was the Deleuzian, post-Marxist philosophers Hardt and Negri that offered the new model of ‘swarms’. This model described the movements of ‘the multitude’, which replaced the working class as the revolutionary subject of a materialist history. What is unique to the new revolutionary subject, is that ‘the multitude’ is not limited by place, or by a single identity. New forms of communication meant people could act together in their irreducible multiplicity. That is, without sharing one identity and one leader.

Hardt and Negri wrote Empire in the mid 90’s between the Gulf War and the Kosovo war. It argued that imperialism was no longer the adequate model to analyse different forms of domination. What was then emerging was a network of powers that function collaboratively. A network of national powers, economic power, international powers, and a decentred networked structure. This ‘Empire’ is a global form of rule that exacerbates, what they called, the degradation of ‘democracy’. This was a time, when democracy seemed to be synonymous with ‘ruled by America’. Hardt and Negri pointed beyond this old system, to the network’s sovereignty which is the larger system in which the older national sovereignty functions. Empire can thus be defined as an emerging condition, and a structure, and an opportunity that radicals are intoned to grasp.

In 2004 they released Multitude. They argued that if, in a globalized world nation states are no longer sovereign, the notion of ‘the people’ aligned to nation states is obsolete. A new concept of ‘the people’ was needed to imagine a network of unbounded agents. The eponymous concept of ‘multitude’ was proposed, and they described the multitude in terms of ‘swarming’ networks. Hardt and Negri wanted to move away from the concept of leaderless organisations, but not on principle as Joreen Freeman had argued 40 years previously.

See:

The Tyranny of Leaderless Activism

Leaderless organisation models became part of the ideology of the women’s liberation movement in the 1960’ and 70’s. It was thought a corrective to an overly structured society and to the resentment at the control others had over our lives. As long as second wave feminism concerned itself first and foremost with consciousness-raising, the model worked f…

Rather, Hardt and Negri argued on pragmatic grounds as political radicals. Movements thus far have failed to hold on to whatever gains they had made. Hardt and Negri were looking for a model of organisation which could sustain political movements. They thus reformulated a perennial problem for the left- ‘how to organise a diverse multiplicity now that ‘working class’ has been diversified and transformed beyond recognition’. In their view, there will be no return to a unitary political subject like the working class, nor to a centralized leadership council, or an electoral party or ‘a people’.

Leaderlessness is the label often given to these uprisings, especially by the media: and indeed they reject traditional forms of centralised leadership, attempting to create new democratic forms of expression. But rather than describing them as leaderless, it is more useful to understand them as multitude struggles- useful, in part because it allows us to grasp both their virtues and the challenges they face.

In making this move, they evade a confrontation with the contradictions of the leaderless model, which appears elsewhere in their approach. They introduced the concept of ‘multitude’ to describe new democratic forms of expression that were in struggles against capital. These struggles were organised by networks online which choreographed protests, or violent disturbance, but could also include a scripted performance or spectacle to raise awareness.

Where ‘the people’ once gathered in protest, now the ‘multitudes’ networked in ‘swarms’.

Twenty years after Empire was published, they argued that this concept marked an alignment with intersectional analyses. The nature of race, class, sex gender and national hierarchies are all recognized as vectors of domination in political analysis. They argue that we need to speak of racial class and sexual class among others in an intersectional analysis of structures of domination. They emphasize that all of these classes are created by their relation to the domination of capital. They are all thus internally related to each other as a result. This is crucial for how the left organises itself. Just being sympathetic to other such struggles, of other classes, is not an adequate response. In fact, it does not make sense for one class to be sympathetic to an other’s struggle, because they are all a moment in the same struggle. This mereological relation, they argue, creates the multitude as an agency, without returning to the unitary political subject.

The left’s critique of swarms: religiosity and absolutization

Despite all this, the question they posed themselves remains the same:

How can a multiplicity act politically, with the sustained power to bring about real social transformation?

We emphasize the main clause above and ask how does the multitude act politically. Our question is not mistaking a project for an empirical phenomenon. For Hardt and Negri, the multitude already exists. Hardt and Negri insist that the movement from working class to multitude has already begun and is ongoing. Intersectional classes are already internally related and thus exist as an empirical phenomenon to be understood. Only they are poorly understood thus far. The question should therefore be, how does a multitude act politically? It is more logical to analyse the empirical world before drawing up a strategy for a political venture. It may also be more ‘useful, in part because it allows us to grasp both their virtues and their challenges they face’ in situ.

Perhaps, it is unfair to criticize Hardt and Negri for not facing the terrifying movements that have aligned themselves with their concepts of multitude and swarm. However, terrifying new forms of expressing empowerment were there from the start, as swarming multitudes. There are many swarms acting in the belief that they are the multitude and the inheritors of a new world, whether they put it in the terms of Hardt and Negri or not. A narrative that grants a claim to the absolute, to be leaderless and absolute sovereign over others.

The emphatic and prophetic prose of Empire betrays a tendency towards the absolute in their approach. It has been subject to an immanent critique which shows how the coming ecstasy of revolution is argued for on the basis of Spinoza’s pantheist philosophy of love: ‘Today time is split between a present that is already dead and a future that is already living… In time, an event will thrust us like an arrow into that living future. This will be the real political act of love’. Speaking for the multitude who organise themselves in anonymous networks online, they often speak with a now familiar disavowed religiosity. The kind of religiosity that many social commentators, psychologists and sociologists are tracking alongside the influence of social media. Jonathan Haidt, for example, uses Durckheim’s analysis of totemic religion, and the concepts of the sacred and the profane to make sense of the polarisation of society and the effervescence of hatred online.

See:

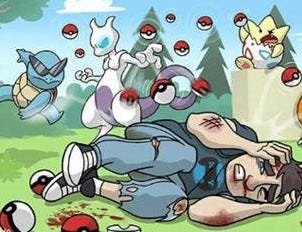

Pokémon Go and Social Justice Games: Online Hate Groups and Offline Violence

Do you remember the Pokémon Go craze of 2016? I am not gamer, but I watched on engrossed, wondering if I was the only one to see a precursor to something sinister. This was a threshold moment, when the surreal and virtual exploded into the actual and possible. Back then, this thought set me at some distance to the gamers and the disdainers alike. News …

Rather than showing concern for the religious enthusiasm for swarms of shaming and violence as a political strategy, Hardt and Negri speak even today as the prophets of a coming oneness. It is worth remembering that Spinoza believed that intuitive prophecy was the basis of true faith, and that ‘a prophet creates his own people’. The fate of the other people is cast off like dice in a zero sum war without responsible leaders.

Hardt and Negri are not the leaders, but rather the irresponsible prophets announcing that some sort of final age has arrived. As Tom Nairn writes in his review of Empire in the LRB Vol. 27 No 9, 5th May 2005.:

It has taken a while for ‘the people’ to show up as global everybody or multitude; but this is good luck for our authors, as they do not hesitate to remind our readers. Thanks to the Western victory in the Cold War and to the information technology, can it be that globalisation is putting whole world into the hands of today’s radical heretics?

While Tom Nairn is perhaps not the fairest reader of a Deleuzian politics (he goes too far in claiming Lacan, Deleuze and Guatarri are on a project of redemption) his critique of Empire does hit home. Some of my fellow Deleuzian post-Marxist Master’s students found the language of Empire a little embarrassing, but that was beside the point, they thought. However, Tom Nairn, a Marxist in the Gramscian tradition, makes clear that a dangerous tendency to the absolute is betrayed by the pervasive prophetic style. However, this is not something they have garnered from Deleuze and Guattari. Indeed, despite first appearances Deleuze is generally considered less radical than many undergraduate’s hope. Many continental philosophers agree with Peter Halward’s critique of Deleuze’s conservative political thought.

That said, some continental philosophers do see a Spinoza inspired spiritualism in Deleuze, and in other thinkers from the 1980’s. Tom Nairn can call upon influential continental philosophers who also argue this case. Julia Kristeva, a French feminist and philosopher of bodily drives, pointed out in 1984 that ‘the latest example of French totalism, a product of the nostalgia for the universalizing vocation of the French intelligentsia, seeking new grounds to assert the prerogatives of its historical role, refusing to allow itself to be consigned to Pareto’s “graveyard of aristocracies”.

The left’s critique of swarms: the disavowal of the disavowal of the political and the Other.

In his review of Empire Twenty Year On, Hardt and Negri plea that intersectional classes should see their own movements as moments of an (ecstatic) whole. Their appeal to Judith Butler’s concept of ‘precarity’ is central to folding the movements of differentiated classes one in the other. I think this is a sincere move and I think Judith Butler’s analyses of precarity should be central to their project. Despite all this, there seems a slight desperate plea to bring post-Marxism, post structuralism, and class back into modern political discourse. Perhaps, a call from Pareto’s ‘graveyard of aristocracies’ where the dead white men of millennia lie parenthetically. While white male Deluzians and deconstructionists are still dancing and celebrating, and calling from that graveyard, the posterity of French feminists like Kristeva and Irrigary are also called into question. Even Judith Butler remains conspicuously quiet on the debates on gender, while she dares to advocate that feminists’ students should still read the dead old white men.

Members of the intelligentsia believe that their particular boundaries are imbued with universal meaning. But the same can be said for religious fanatics. Today nationalism- in Modi’s Hindus, Orbán’s Hungarians, Netanyahu’s Israelis and Putin’s Russians- is capable of stoking a religious enthusiasm as Hardt and Negri do. These boundaries must be fought for. There is always someone or somewhere else or other. Empire now seems no less naïve a book for supplanting national sovereignty and ‘the people’ for ‘empire’ and ‘multitude’, than Fukuyama did for proclaiming the end of history.

In his critical review, the late Tom Nairn argued for the importance of nations for achieving ‘self-determination of the proletariat in each nationality’, ‘in isolated and exceptional cases’ first and then developing in solidarity with others. However, the dynamic of political history he describes also describes the inherent shifting particularities of a tribal society well. It serves well as a critique of the naiveté of Empire and the religious desire for the absolute that effaces the everywhere and everyone else. This naiveté masks the construction of a disgusting other.

the actual touchstone of actual political history would appear still to be somewhere specific… rather than up in the ether of universal being and implication. And somewhere always somewhere else: recalcitrant, differing elsewhere, beyond this or that boundary- or possibly (one suspects) beyond every one of the frontiers and diverse identities that have so far, structured a necessarily disruptive and nomadic species.

It is in this barbarism of warring tribes that Hardt and Negri celebrate the multitude, as a multitude of signs of grace and redemption. It is paradoxically the religiosity in the belief in the absolute Oneness and the Good of one’s swarm that propels this barbarism. The moral emotions of their multitude, and those of identity politics they align with, coalesce with right wing nationalists who reject ethical responsibility to the Other on the bases of their own tribal identity. All believe that their swarm is good and this fact bestows ethical privileges. For one thing, their enemies are not deserving of basic rights, let alone equality. Is it too much to say that the prophets of the multitude bestow these privileges by announcing the multitude. By choosing not to use the term leaderlessness, but to look at the virtues and challenges facing each struggle and call it a moment of the multitude(s). To face the challenges that they are facing as one’s own. As challenges to one’s own virtues and one’s own struggle. But are all multitudes good? Are all swarms good?

Rancier’s critique of the concept of ‘multitude’ is along similar lines. The concept denies the nature of politics. The concept of ‘multitude’ denies that politics is something different from metaphysics by claiming ‘everything is political’. It is the fact that they deny the distinction between who is equal and who is not, or who is the people of equals, that is at the heart of politics. This allows them to treat the Other irresponsibly because the other is effaced in the myth of leaderless activism. They can claim to be leaderless, that is, without distinction, while the leaders make this distinction in the shadows. Rancier’s critique of the concept of ‘multitude’ and it’s replacement of the concept of ‘the people’ is expressed with the simple question:

Did the Arab crowds applauding the Twin Towers carnage in the name of Allah constitute an example of the ‘multitudes’? And are all multitudes ‘good’ or true ‘multitudes?’

Not surprisingly, the authors of Empire argue that the multitude becomes political, in the sense of acting with the sustained power to bring about real social transformation, “when it starts to confront the central, repressive operations of Empire directly and with an adequate consciousness”. It is hard to see how drugging, robbing, sexually harassing and sexually assaulting the only foreigner working in a café for under minimum wage, someone stuttering in a foreign language far from friends and family while a student in Berlin, is in any way tackling ‘the central repressive operations of Empire’. Even if we were to concentrate on the adequate consciousness and consider my position in relation to the different intersectional classes, it is hard to see how my treatment can be justified. I was housed in a flat in Berlin to be drugged for a few years. This eviscerated the emotional life that I grew up with. In truth, they are targeting some of the most vulnerable people that they can still claim are privileged, privileged for being white educated male Brits. These swarms anonymize and celebrate the dehumanization of scape goats while dissimulating their abuses with the myth of leaderlessness. Everybody in the group chat thinks they are equal, that is the mantra, and that is their metaphysical belief. In truth, even the members of the group chat and Telegram channel are victims of the administrators in control. The actors in these swarms know even less than the victims, not despite, but because they are sent the script of ‘political’ abuses, because everything is political.